The Original Tartan Army

kilts in the highland regiments

‘Tartan’, a major exhibition curated by the V&A Dundee, will open to the public in April 2023. The Highlanders’ Museum has loaned several pieces of this iconic material to the exhibition and to mark the occasion our first blog of the year attempts to answer the often asked question “why did Highland Regiments wear kilts”?

One of the most common questions asked by visitors to the museum is why Highland regiments wore kilts, and how practical was it to do so? The answer partly lies in the Government response to the Jacobite rising of 1745/46. The fact that most of Prince Charles’ support had come from Highland clans rattled the political establishment in both London and Edinburgh, and measures were taken in the aftermath of Culloden to break-up the traditional Clan hierarchy. In particular, the Dress Act of 1746 specifically banned the wearing of the kilt by stating that:

“No man or boy within that part of Britain called Scotland, other than such as shall be employed as Officers and Soldiers in His Majesty’s Forces, shall, on any pretext whatever, wear or put on the clothes commonly called Highland clothes (that is to say) the Plaid, Philabeg, or little Kilt, Trowse, Shoulder-belts, or any part whatever of what peculiarly belongs to the Highland Garb; and that no tartan or party-coloured plaid of stuff shall be used for Great Coats or upper coat”

Penalties were harsh, six months imprisonment for a first offence, transportation for a second. But the crucial exception “other than Officers and Soldiers in His Majesty’s Forces” allowed loyal Clan chiefs, or the sons of chiefs who had supported the rising, to curry favour with the Government by raising Regiments of Foot in the King’s service.

When the 72nd, 78th and 79th Highlanders were raised in the late 1700’s, the standard dress was still the belted plaid, a single piece of tartan combining kilt and cloak. By the start of the Napoleonic wars the regiments had adopted the more practical philibeg (from the Gaelic feile-beag, or little kilt), similar to the kilt worn today. By 1809, five regiments wore the kilt: the 42nd (Black Watch), 78th (Ross-shire Buffs), 79th (Camerons) 92nd (Gordons) and 93rd (Sutherland) Highlanders. After the Battle of Waterloo in June 1815, the reputation of Highland Regiments, and by extension the aura surrounding the kilt, was cemented in public and Government opinion by Wellington’s Waterloo Despatch which stated “The troops of the 5th Division, and those of the Brunswick Corps were long and severely engaged, and conducted themselves with the utmost gallantry. I must particularly mention the 28th, 42nd, 79th and 92nd regiments, and the battalion of Hanoverians”.

Sergeant Thomas Campbell of the Grenadier Company of the 79th recalled being summoned to meet the Emperor of Russia, two months later in Paris, for a detailed inspection of the kilted soldier “he examined my hose, gaiters, legs, and pinched my skin, thinking I wore something under my kilt, and had the curiosity to lift my kilt up to my navel, so that he might not be deceived” [1].

Sir Walter Scott’s grand Edinburgh pageant for George IV in 1822 further enhanced the image of the kilted warrior and by the time Queen Victoria purchased Balmoral in 1848, the reputation of the rebellious Highlander had completely reversed to one of romantic curiosity touched with a discreet respect.

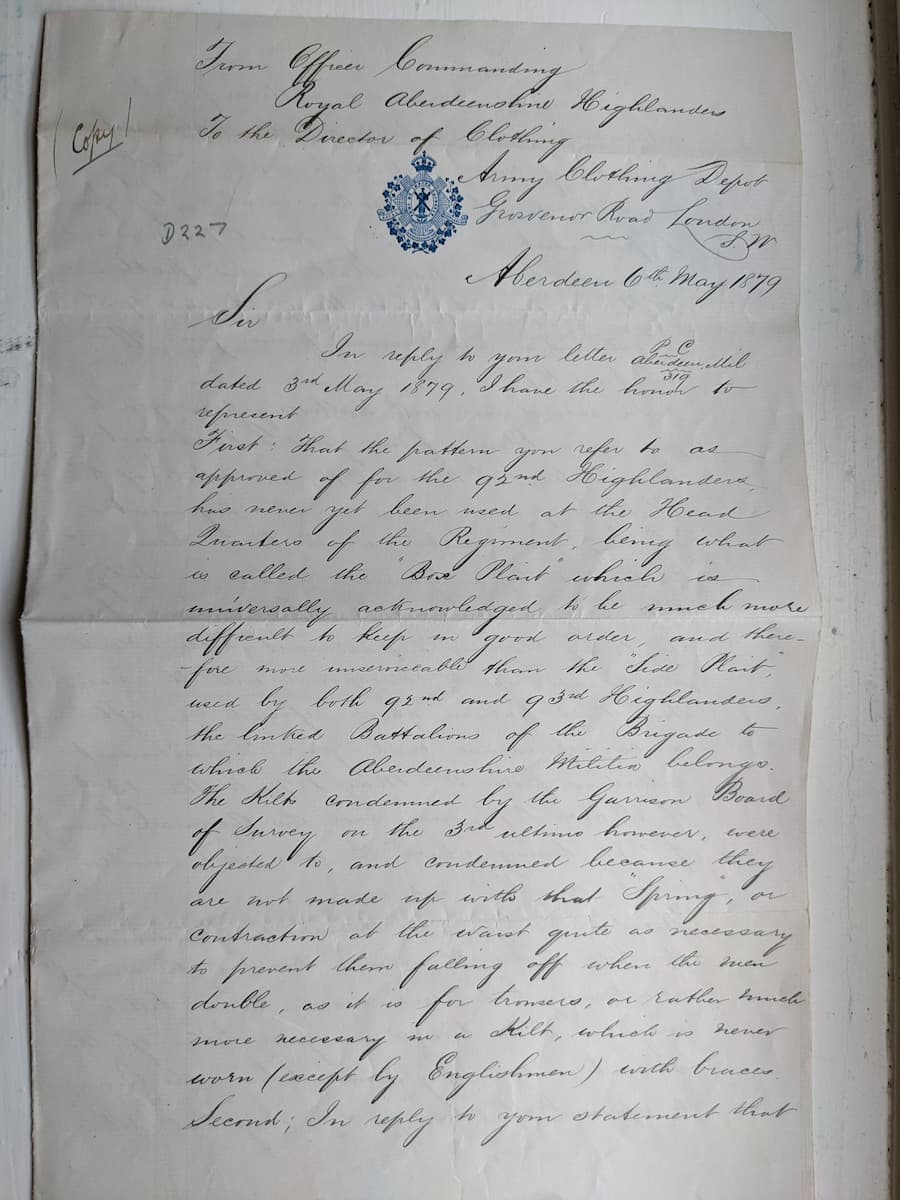

Whilst the kilt was now accepted as the uniform for Highland regiments, it was undoubtedly more expensive to kit out and the Army Commissariat were always looking at ways to reduce the cost. In May 1876 a rather irate Colonel of the Aberdeenshire Highlanders, later to become the 3rd Battalion Gordon Highlanders, wrote to the Army Supply Department in London expressing his concerns at the quality of the kilts supplied. Amongst several complaints was that “they are not made up with that “Spring” or contraction at the waist quite as necessary to prevent them falling off when the men double, as it is for trousers, or rather much more necessary in a Kilt, which is never worn (except by Englishmen) with braces”. He concluded his letter by stating that “the Kilts, Gaiters, Trews and Feather Bonnets of a Highland Regiment can never be properly made up in London, but only at the Depots and Headquarters of the Kilted Corps”. His advice was heeded and to this day there is a Tailors Department at Fort George to meet the requirements of the garrison.

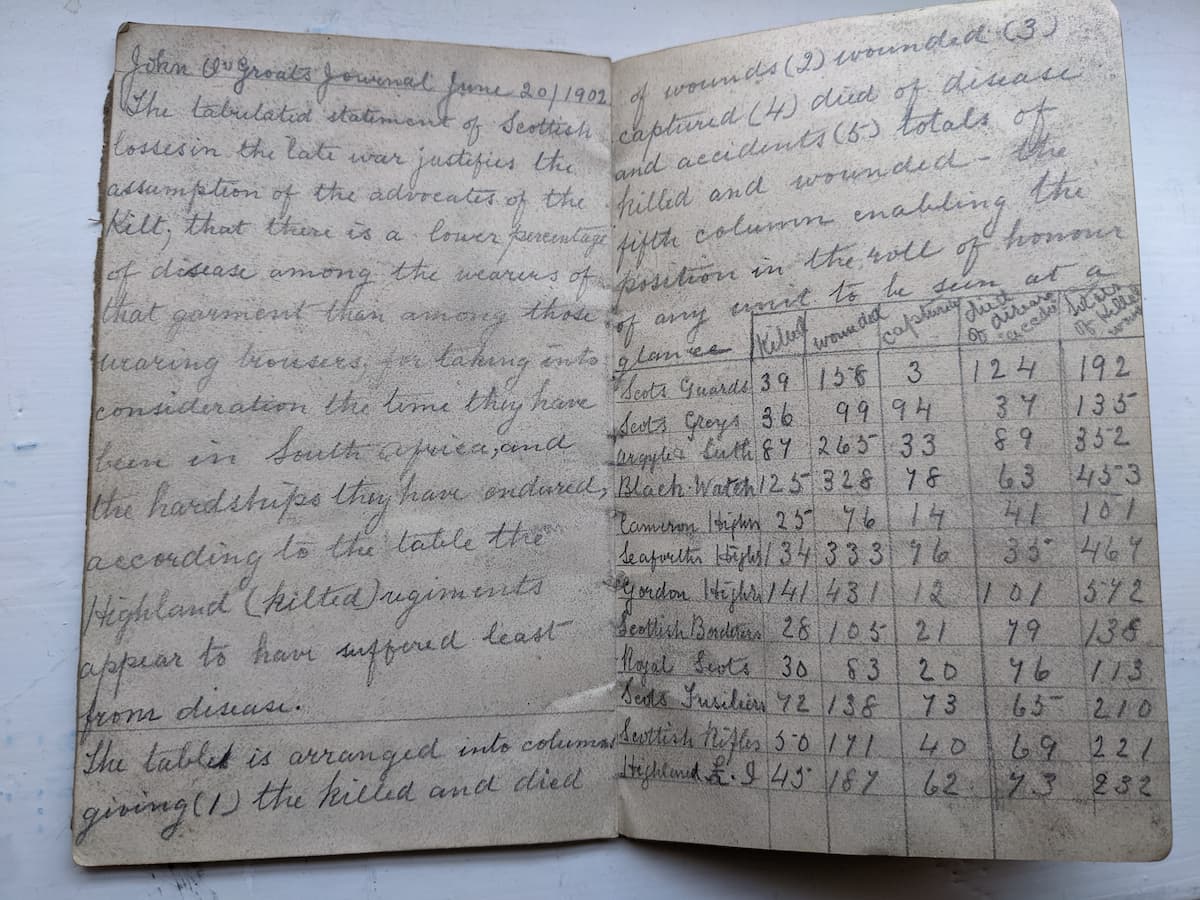

As the 19th Century progressed and the range and accuracy of rifle fire became more lethal, the conspicuous scarlet jacket worn by all regiments was abolished and khaki was adopted for active service in time for the Boer war of 1899 – 1900. In the case of the kilted Highlanders, a khaki apron was introduced to wear over the tartan kilt. By the end of the Boer war, the practicality of the kilt on active service was beginning to be questioned more widely. Perhaps as a counter to this, the John O’Groats Journal in June 1902 published “the tabulated statement of Scottish losses in the late war justifies the assumption of the advocates of the kilt, that there is a lower percentage of disease amongst the wearers of that garment than among those wearing trousers, taking in to consideration the time they have been in South Africa, and the hardships they have endured, according to the table the Highland (Kilted) regiments appear to have suffered least from disease”.

Private James Lyon of 2nd Seaforths, obviously agreed as he copied out the article in full into his notebook, where he also kept a meticulous record of each day’s march from his arrival South Africa in 1899 to the end of the war in May 1902.

It was not until WWI that the kilt was seriously questioned for active service, when many new Highland battalions were being raised. These battalions were largely filled with officers and men straight from civilian life who had never previously worn a kilt, and as might be expected, there was plenty of grousing regarding the dress and its usefulness in war. Common complaints were chaffing of the back of the knees when wet, fondness of lice for breeding in the deep pleats, and catching more easily than trousers on barbed wire.

Conversely, in cold, wet trenches deep in mud, the kilt was found to be warmer than sodden, wet khaki trousers. This was partly due to the fact that kilts were easily removed to keep them dry when trudging up and down the long communication trenches, unlike trousers which required boots and puttees to be taken off first.

Then, in 1917, the Germans used mustard gas for the first time, which is not only highly toxic but causes painful blisters on contact with bare skin. Some medical authorities now argued that the bare legs of the Highlanders led to unnecessary casualties; others believed that the seven yards of thick tartan around the middle offered better protection than trousers, and a contaminated kilt could be discarded more quickly. These arguments for and against had still not been resolved by the time hostilities ceased in November 1918.

Although the inter-war years 1919-1939 saw Highland battalions posted as far afield as India, Myanmar (Burma), Shanghai, Sudan, Egypt, and Palestine, there was relatively little fighting and apart from hot summers when shorts were worn, the kilt continued in use. But by the late 1930’s, as war loomed once again, those Highland officers at Staff HQ defending the kilt found themselves in a much weaker position than 1914. For it could not be denied that whereas during WWI most soldiers still marched to battle on foot, by 1939 the use of motor vehicles and even the possibility of air transport was becoming a reality, for which the kilt was not so suitable.

It followed that within a few months of the outbreak of WWII the use of the kilt on active service was abolished. As it happened, the 1st Cameron Highlanders were mobilised to France within a few weeks of the outbreak of war and before the order proscribing the kilt had been issued. So it was that the Camerons had the honour of being the last Highland regiment to wear the kilt in combat, when on 25th May 1940, they held off an attack by around 300 German tanks on a defensive position on La Bassee canal, on the retreat to Dunkirk. An event proudly reported in the Aberdeen Press & Journal, which quoted a ‘young Glasgow Cameron’ recounting “At Louvain, when battle was imminent, the order was given for every man to shave and put on his kilt. Shortly afterwards the Camerons went into action – went in, as the Glasgow man said ‘with pleasure’”.

Thereafter, most officers in a Highland regiment took their kilts on active service and on suitable occasions, when not engaged in actual fighting, wore it proudly. To this day, the tartan kilt remains one of the most distinctive uniforms in the British Army. To quote one of its fiercest advocates, Major General Douglas Wimberley, CB, DSO, MC, affectionately known to the men he commanded in the 51st Highland Division as ‘Tartan Tam’, “Whether in peace or war, a regiment that parades in the kilt cannot be mistaken by friend or foe alike” [2].

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)

[1] Highland Soldier 1820 – 1920, Diana Henderson, John Donald Publishers, Edinburgh, 1989

[2] The Kilt in Modern War, Major General (retd.) Douglas Wimberly, unpublished memo, Coupar Angus, November 1979 (QOCH collection)