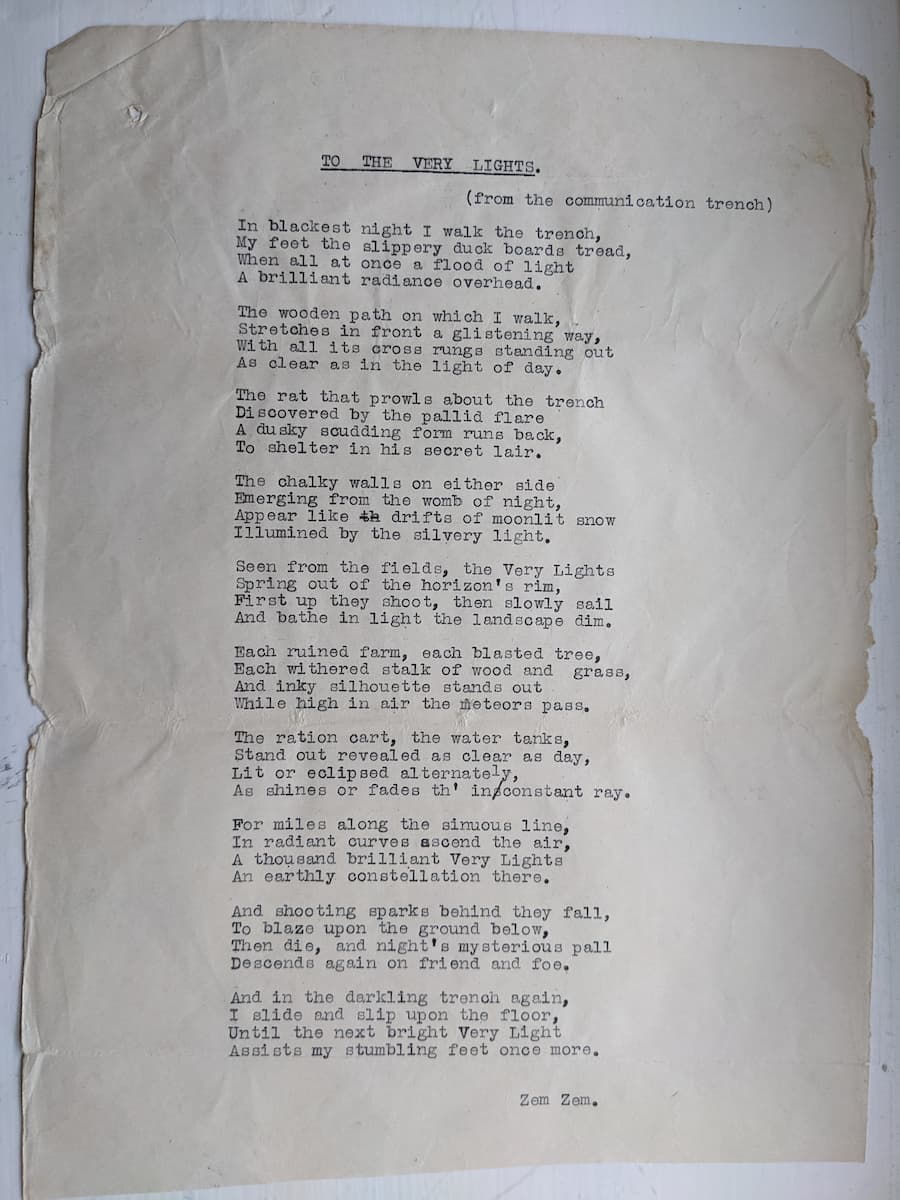

To The Very Lights

A poem by Zem Zem

Zem Zem Anthology #3

One of the regular tasks of a Pioneer battalion was to construct and repair the miles of trenches that linked various trench systems running parallel to the front line. These narrow communication trenches enabled troops from rear areas to get to the front without exposing themselves to artillery or sniper fire. With the German front line often occupying the high ground and spotter aircraft active during the day, trench construction was best done under the cover of darkness. The 9th Seaforth’s war diary entry for 23rd-29th January 1916 records a typical week’s work:

“A.Coy. Engaged in revetting and wiring work in communication trenches. 1 Platoon in dug-outs at Moated Farm reclaiming Lone Farm Avenue. B.Coy. 2 Platoons working by day and 2 Platoons by night repairing communication trenches. C.Coy. working at Div(ision) Grenade school. D.Coy engaged by night draining front line trenches.”

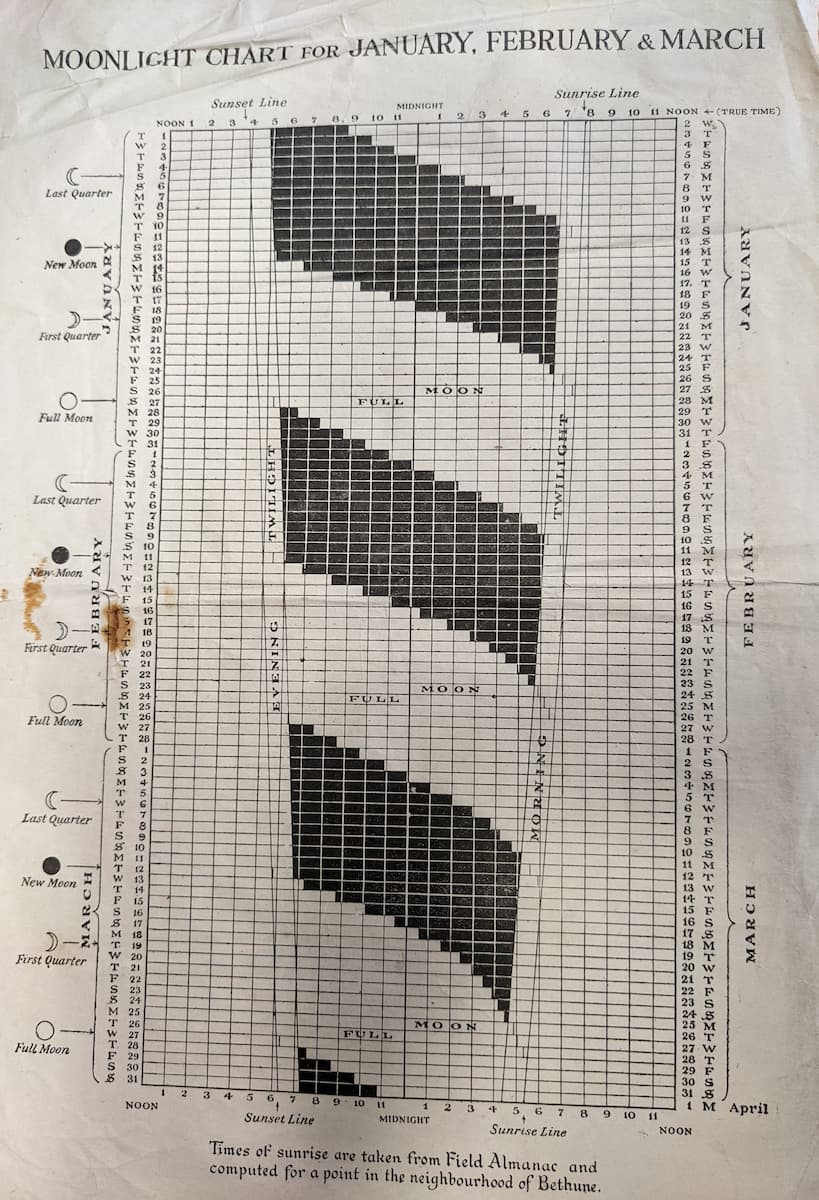

To help plan the work, a so-called Moonlight Chart was used to determine the number of hours available to carry out any clandestine operations during a new moon, or nights of better visibility for trench construction when the moon was full. In the total absence of any light from the ruined towns and villages, both sides used flares to illuminate and catch out each other’s night-time activities.

To the Very Lights

(from the communication trench)

In blackest night I walk the trench,

My feet the slippery duck boards tread,

When all at once a flood of light

A brilliant radiance overhead.

The wooden path on which I walk,

Stretches in front a glistening way,

With all its cross rungs standing out

As clear as in the light of day.

The rat that prowls about the trench

Discovered by the pallid flare

A dusky scudding form runs back,

To shelter in his secret lair.

The chalky walls on either side

Emerging from the womb of night,

Appear like drifts of moonlit snow

Illumined by the silvery light.

Seen from the fields, the Very lights

Spring out of the horizon’s rim,

First up they shoot, then slowly sail

And bathe in light the landscape dim.

Each ruined farm, each blasted tree,

Each withered stalk of wood and grass,

And inky silhouette stands out

While high in air the meteors pass.

The ration cart, the water tanks,

Stand out revealed as clear as day,

Lit or eclipsed alternately,

As shine or fades th’ inconstant ray.

For miles along the sinuous line,

In radiant curves ascend the air,

A thousand brilliant Very lights

An earthly constellation there.

And shooting sparks behind they fall,

To blaze upon the ground below,

Then die, and night’s mysterious pall

Descends again on friend and foe.

And in the darkling trench again,

I slide and slip upon the floor,

Until the next bright Very light

Assists my stumbling feet once more.

Zem Zem (undated)

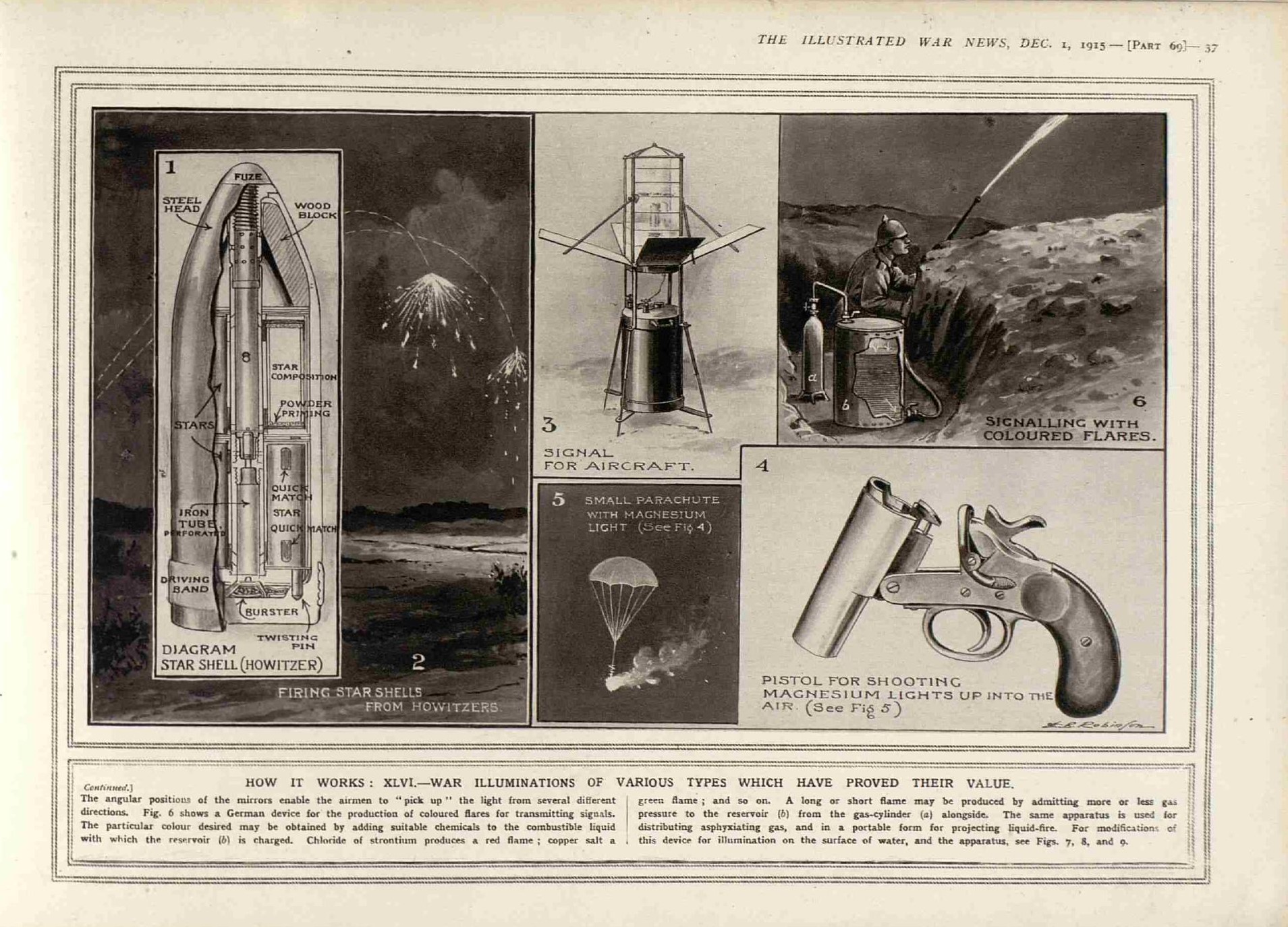

The Illustrated War News, a wartime subsidiary publication of the Illustrated London News, carried a regular ‘How It Works’ feature and the December 1915 edition covered War Illuminations, describing the various pyrotechnics used to light up the battlefield. One method was the star shell, fired from a field gun and filled with up to eight cartridges that burned brightly as they fell towards the ground. A single shot version, fired from a hand-held pistol, used a burning piece of magnesium suspended from a small parachute to provide near instant light as it slowly drifted towards the ground. The British called these flare guns Very Lights, after the inventor Edward Wilson Very, an American Naval Officer, although most were supplied by the pistol manufacturer Webley and Scott.

In a letter to the Bellshill Speaker, printed in July 1915, Drummer Michael Tracey explained the dangers posed by star shells: “As the 9th Seaforths are a pioneer battalion, we have to run some great risks… As soon as the star shells go up we have got to get down and lie flat, so as not to be seen by the enemy, as sometimes they send over a hail of bullets trying to cop us, but we are too quick for them”.

A popular song with the soldiers, sung to the tune of ‘When Irish Eyes are Smiling’, highlighted the dangers in slightly coarser language:

When Very lights are shining,

Sure they’re like the morning light

And when the guns begin to thunder

You can hear the angel’s shite.

Then the Maxims start to chatter

And trench mortars send a few,

And when Very lights are shining

‘Tis time for a rum issue.

When Very lights are shining

Sure ’tis like the morning dew,

And when shells begin a bursting

It makes you think your times come too.

And when you start advancing

Five nines and gas comes through,

Sure when Very lights are shining

‘Tis rum or lead for you.

Very lights featured in other published references. A staff correspondent of the United Press, reporting from the trenches, noted the wry humour of the British Tommy: “At one circular cluster of dugouts was a sign reading ‘Piccadilly Circus’… ‘Tourists welcome’ said another. ‘Very lights, three pennies’ read another”. Bruce Bairnsfather, a prominent humourist and cartoonist of the time, regularly drew the arc of a Very light to indicate night-time in his ‘Fragments from France’ series of cartoons published weekly in The Bystander magazine during the war.

Zem Zem’s poem ‘to the Very lights’, written from the view point of a communication trench, is a new addition to the genre and perfectly describes the paradox between the serene beauty of a flare arcing into the night sky and the mud, detritus, and destruction lit up below.

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)