From Seaforth to Air Force

A Soldier Takes Flight

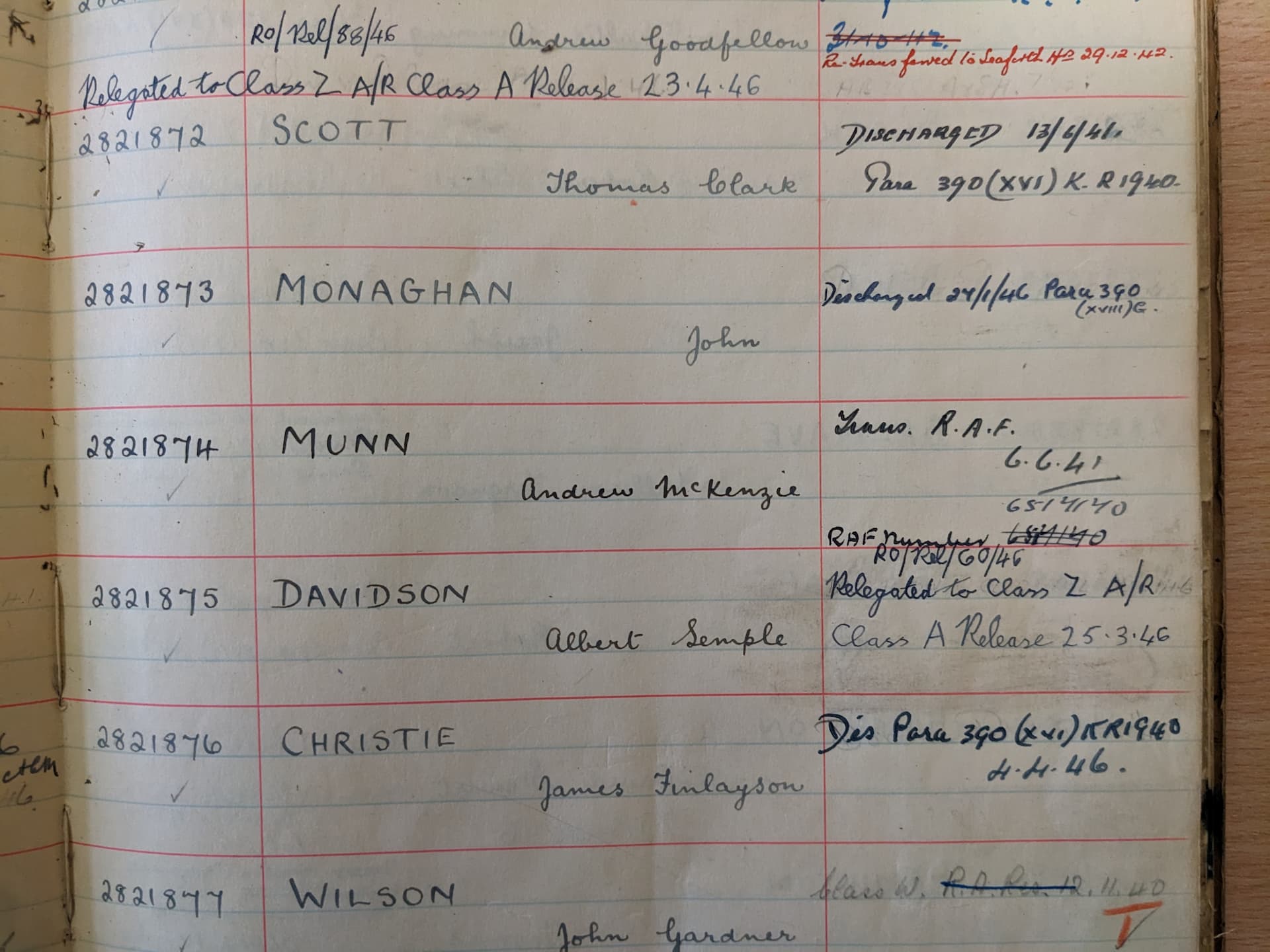

At 20:18 on the evening of 13th April 1943, a Lancaster MkI of Bomber Command’s 103 Squadron rolled down the runway at RAF Elsham Wolds and took to the Lincolnshire skies, laden with a 6000lb bomb load. Target that night: La Spezia, a port in Northern Italy. Over 1000 miles from Elsham Wolds and at the limit of the Lancaster range, it was a daunting 10 hour round trip but to the men onboard aircraft number W4828 ‘E for Edward’ it made a welcome change to the heavily defended German cities that had been targeted repeatedly over the previous months. Tail-gunner Sergeant Andrew Munn had joined the squadron in February and was on his 14th sortie. Unusually amongst RAF crew, three years earlier as 2821874 Lance Corporal Munn of 6th Battalion Seaforth Highlanders, he had been on the receiving end of bomber attacks on a different port entirely: Dunkirk.

So how did this erstwhile Seaforth Highlander come to be sitting in the rear gun turret of a Lancaster bomber? Thanks to his diary, notes and photographs which were donated to The Highlanders’ Museum by his nephew, we have been able to piece together a few details about his life and escapades that lead up to that fateful evening 80 years ago.

Andrew McKenzie Munn was born at Bellwood Cottage, Barnhill, Perth on 6th September 1918, the third child of William Munn and Helen McKenzie. His father was a Press Association photographer and one of the pioneers of the then relatively new art of press photography. Andrew attended Balhousie Boys School in Perth, where he was good at sports and an above average scholar. On leaving school he worked as a salesman and it was whilst driving a van in that capacity that he had his first lucky escape when another vehicle lost control in snowy conditions and crashed into him. Six people, including his younger brother, his sister and her baby were taken to hospital although Andrew’s injuries were only minor.

In July 1939 with war clouds looming, he joined the Seaforth Highlanders and after six weeks square bashing at Fort George, was assigned to a Bren carrier platoon. He was posted to the newly formed 6th Seaforths and in January 1940 they mobilised to France to join the British Expeditionary Force. During the German advance into the Netherlands in May, the battalion held positions in Belgium and then on the River Scarpe, near Arras. It was during an Allied counter attack on 27th May that Andrew had a second lucky escape when a bullet struck him in the thigh, painful but not serious. He was evacuated to Dunkirk but his troubles were not yet over. In his diary he writes:

“May 31st: After travelling 10 miles in 15 hours boarded boat “Crested Eagle” in morning. Afternoon 2 o’clock bombed 5 miles out by dive bombers. Had to leave ship and swim to beach. Spent horrible night on beach as all our clothes wet.”

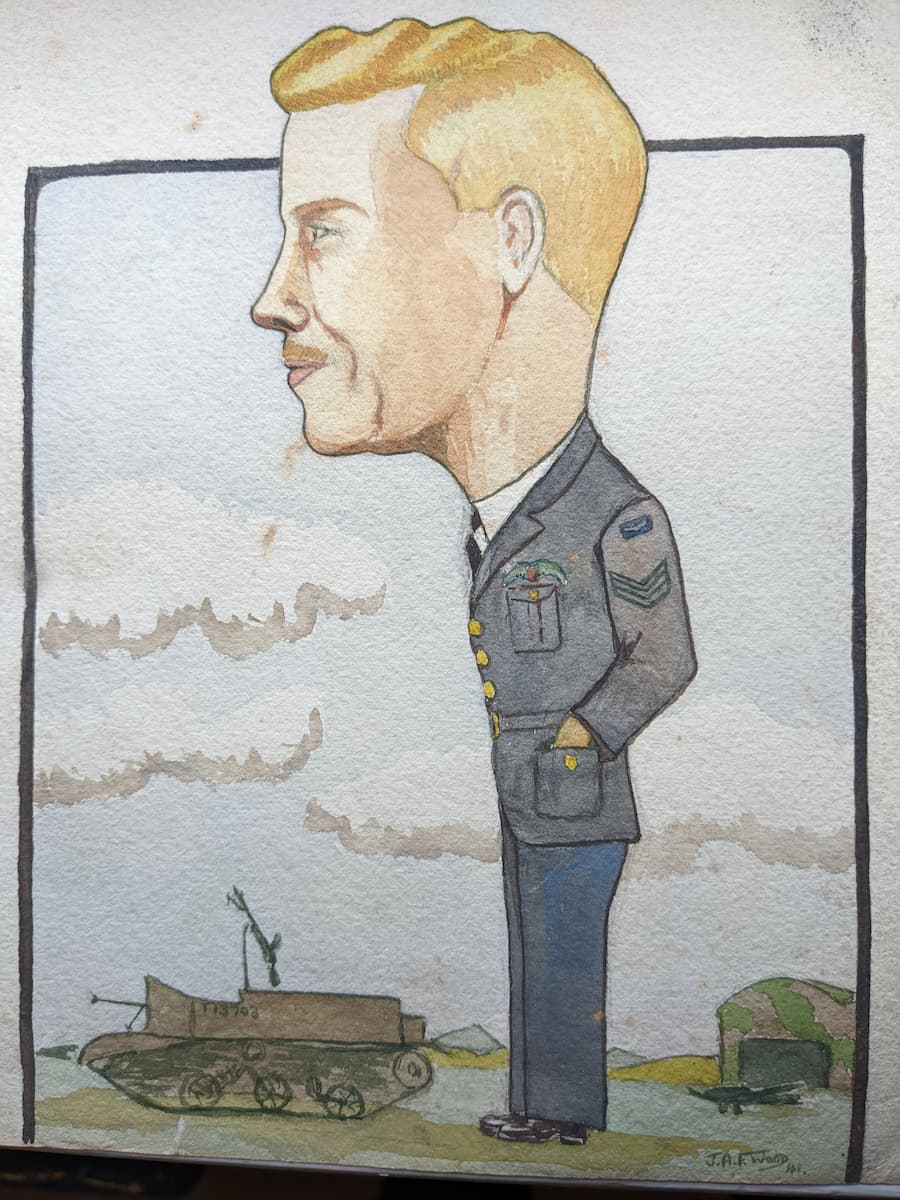

The following day, after a nerve-wracking transfer to a waiting destroyer, he was landed at Dover and transferred to a military hospital in Sheffield. A photograph taken whilst recuperating there shows that he clearly enjoyed the attention of the nurses during his stay, but he was soon discharged back to 6th Seaforths where “for the first time they knew I was still kicking”. Perhaps it was when he “discovered that about 200 of the boys got back, notice a lot of new faces” that he decided he would prefer to be dropping bombs not dodging them. He put in a request to transfer to the RAF and after a spell in the garrison at Enniskillen, Northern Ireland, where he “did nothing for about a month but fish and swim -Brr”, this was duly granted on 6th June 1941. Before he left for the RAF his friend and fellow Dunkirk evacuee James Wood* sketched him in caricature as a dashing RAF pilot, with a Bren gun carrier in the background to remind him what he was giving up!

He was posted to No 9 Initial Training Wing at the Arden Hotel, Stratford-on-Avon, for six weeks square bashing RAF style. Up at 6, bed stripped and kit stowed before breakfast, then on parade by 7. Physical training, route marches and cross country runs interspersed with lectures on the principles of flight, navigation, aircraft recognition, Morse code, wireless communication and much else besides filled the rest of the day.

Square duly bashed, it was on to initial flight training. The threat of Luftwaffe raids, poor weather and lack of aircraft in the UK meant that this was conducted in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Cadet Munn was duly shipped across the Atlantic to No.1 Manning Depot in Toronto, Canada.

(* James Alexander Fraser Wood (1918 -1984) was a farm labourer, Seaforth Highlander, mechanic, deep sea fisherman and revenue officer but is best known as an author of novels and short stories about life at sea. He was born, raised, lived and died in Elgin, Morayshire.)

The Manning Depot was essentially a repeat of the training in Stratford except that after five weeks, a selection committee decided whether the trainee would be placed in the aircrew or groundcrew stream. Andrew was deemed suitable for aircrew and was sent to No.2 British Flying Training School in Glendale, California. Three weeks of ground school were followed by eight weeks pilot training interspersed with trips to Long Beach and Hollywood on days off. His flying skills gradually improved but by his own admission too many late nights, hangovers and good weekends resulted in being dropped from the course, or in his own words “Washed out (tough)”.

Sent back to Canada and the No.10 Bombing and Gunnery School at Mount Pleasant, Prince Edward Island, he had the shock of Xmas 1941 in a dry county but made up for it at New Year “as we collected some ‘mountain moonshine’ from a local grocer”. January to March 1942 was spent “skating and working” followed by two weeks leave in Montreal. Once again enjoying himself a bit too much, he was four days late reporting for the next course on Air Navigation, earning 14 days CC (Confined to Camp). After a final course at No.3 Wireless Air Gunner School in Winnipeg, 6517170 A.M.Munn was presented with his Sergeant stripes* and Air Gunner flying badge on 31st May 1942, almost a year to the day since joining the RAF.

Granted 10 days leave before returning to the UK, he visited Boston, Massachusetts where he notes “met Irene and went into flat spin. Still in it” and was “sorry to go” when he departed for Halifax and a ship home. The mysterious Irene was soon forgotten however as he “had good 1st Class cabin and it was a grand trip (nurses onboard)”.

(* From May 1940 the Royal Air Force introduced a minimum rank of sergeant for all aircrew.)

Disembarking at Port Glasgow on 30th June, he was sent to Bournemouth “a nice town” where he “settled down (in more ways than one)” but not for long before being sent to RAF Stormy Down, in Wales, for more Air Gunnery training. Then on to the last stage of training at No.30 Operational Training Unit (OTU) at Hixton, Staffs. OTU’s were where the different flying trades came together and trained as a single crew. Bomber crews were self-selecting and generally followed the pattern of one or two men who knew each other deciding to fly together then looking for other members from different trades to team up with. So it was that Sergeant Munn teamed up with Flight Lt. Edward Lee-Brown (pilot), Sgt George Houliston (Flight Engineer), Warrant Officer James Toon, RCAF (bomb aimer), Sgt James Smart (navigator), Flight Sgt James O’Brien (wireless operator), and Sgt Stanley Moseley (mid gunner).

They were posted to 103 Squadron in January 1943 and flew their first operational mission on 4th February, a fairly straightforward run to a so-called ‘fresher’ target at the port of Lorient, in Brittany. There followed 13 more operations to Bremen, Nurnberg, Munich, Stuttgart, Keil, Essen, Duisberg and Berlin before the Spezia raid on 13th April. Targets in northern Italy were viable now that Allied success in North Africa meant that alternate, diversionary airfields were available in Tunisia (although parachuting and capture in France seems a better option that a watery ending in the Mediterranean if the pilot misjudged it).

103 Squadron despatched 20 aircraft on the raid to La Spezia, arriving over the target in the early hours of 14th April. Despite initially heavy flak, the aircraft released their bomb loads from a relatively low level 10,000 – 12,000 ft resulting in multiple fires on the ground and heavy damage. 18 aircraft landed safely back in England and one ditched in the channel 50 miles off Falmouth after the fuel tanks were punctured by flak. The crew were rescued, unhurt, after four hours in a dingy.

One crew failed to return. W4828 came down over Saint-Mars-d’Outill after what was believed to be a collision with an aircraft from another squadron. There were no survivors. Sergeant Gunner Andrew Munn, aged 24, was later buried alongside his six crew-mates in Le Mans West War Cemetery. Four months after the crash his brother Robert and sister-in-law Mary had a baby boy, naming him Andrew McKenzie in memory of the uncle he would sadly never meet.

For several years after, on the anniversary of his death, his family posted a notice in the Perthshire Advertiser in remembrance of a life cut short. Here at The Highlanders’ Museum we are proud to mark the 80th anniversary of a life not just cut short but to remember a Seaforth who chose to live his life to the absolute full.

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)