Scenes from the Somme

Poem from the Archive

The Battle of the Somme was a series of engagements fought over a 25 mile front straddling the River Somme between 1st July and 18th November 1916. Intended as a joint British-French offensive to smash through the German defences and break the deadlock on the Western Front, today it is a byword for the unimaginable loss and futility of WWI.

The 9th Seaforths were attached to the 9th (Scottish) Division, comprising three Brigades: the 26th, made up of Highland regiments including 7th Seaforths and 5th Cameron Highlanders, 27th made up of Lowland regiments and the 1st South African Brigade on what was their first major engagement.

In mid-June 1916 the battalion were moved up from Morbeque, in the BEF reserve area, to Bray-sur-Somme where the British and French armies met. They spent the weeks leading up to the start of the offensive digging support trenches, clearing roadways and constructing dug-outs. On the morning of 1st July the battalion was split up in support of the brigades – A and C companies attached to the 27th Brigade, B Company to the 1st South African and D company assigned the complex task of maintaining the Division’s fresh water supply of around 10,000 to 15,000 gallons (45-68 cubic metres) per day. This was initially done by water tanks on trolleys until the pioneers re-instated the 4” mains line from the pumping station at Suzanne on the river Somme.

LINES TO THE RIVER SOMME

Round the quickly racing river

Woods erect their awning cool.

Reed beds in the heat a-shimmer,

Lillies gem the quiet pool.

In the cool but turbid current

Plunge the swimmers, light of soul,

Sunshine gilds the spacious valley,

Freshly green the uplands roll.

In the street, the endless traffic

Crawls the crowded village through.

Limbers, guns and ammunition

Shells immense, astound the view.

Shouting men and neighing horses

Slowly pass the livelong day.

Clouds of dust the air obscuring,

Thick with dust each narrow way [1].

Up the steep and chalky hillsides

Toil the khaki and the blue [2],

Trails the transport of the armies

Trails the ammunition through.

High in the air the gas bags tethered

Vigil o’er the armies keep,

Droning through the highest ether

Aeroplanes supremely sweep.

All the rolling landscape blazes

Bright with flowers of varied hue

Scarlet poppies, dainty daises

Cornflowers of divinest blue.

Looking northward from the highway

See the lopped trees torn away,

Montauban the ruined screening

Woods of Trones and Bernafay [3].

In the foreground little copses

After seats of learning called [4],

Belch and vomit tons of metal

Ears are deafened and appalled.

Round the planes start shrapnel cloudlets

‘Gainst the blue and white as snow,

Screaming loud the shells go speeding

Bursting far upon the foe.

From afar a whisper rises

Gathering in intensity,

Rising in its pitch and volume

Till a shriek it seems to be.

Tons of earth and stones, and fragments

With a bursting sound of doom,

Leap aloft and hang in azure

Spreading like a sable plume.

Up the slope that fronts the firing line,

A dead Bosch lies, with huddled limbs asprawl

And blackened face, with tight drawn parchment skin

And grinning mouth, unburied now for long.

With angry sneer and outcry petulant

The frequent shrapnel o’er the ragged wood

Lashes its whip, while round the busy dump

The shells throw up enormous heaps of earth

And sink their noses in the muddy soil.

Yet once at eve the bitter wind that blew

For ever from the North died gently down

The clouds departed and the setting sun

Appeared above the splintered woods that cloths

Bazentin’s tortured hills [5]: the air was keen

And touched with frost. Slow sank the sun

Mid orange glories from a primrose sky,

The shattered woods turned purple and the earth

Took on a dim and purple hue and veiled

Her sad infirmities from human eyes.

The glittering constellations slowly wheeled

Their way across the heavens, as of old

They did before the advent of the war,

Unchanged, untouched by man’s adversities

As by his joys and pleasures, calm, serene,

Unearthly in their grand celestial sweep.

While high in Heaven, resplendent, paramount,

Bright Jupiter aloft in Aries shone

Treading the star bespangled zodiac

That marks his ceaseless circuit of the sun,

As far remote the ancient Saturn too

The God of happier days [6], with leaden eye

In orbit slow, revolved, deliberate.

But long ‘ere morn the cruel arctic wind

With its attendants, icy rain and mud,

Resumed its sway: and all night long the stream

Of sick and wounded men poured down the road

The ambulances ploughing through the mud

In blackest night arrived, and by the light

Of lamps and torches, in that bitter rain,

The wounded on their stretchers were brought up

And placed within; then jolting down the road

They took their painful way to Bazentin.

And what a vast of men lie buried here

Beneath these muddy fields! What hopes, what fears

Have here their grave! Oh, will this seed give birth

Like Colchian dragon’s teeth to armed men [7]

To torture generations yet unborn,

Or will a new and better Europe rise

Purged of its dross, by battle purified?

Zem Zem

Villers au Bois 20.10.16

Read notes

1 The first two verses are most likely referring to Bray-sur-Somme, located approximately 5 miles behind the British front line of 1st July 1916 and a key logistical hub in the weeks before the start of the battle.

2 British uniforms were khaki whilst the French wore blue. The River Somme formed the boundary between the two armies, and the 9th Seaforths were located around the town of Bray-sur-Somme in early July 1916, so Zem Zem would have seen plenty of men in French uniforms.

3 The capture of the village of Montauban was one of the few successes on the first day of the battle. The small woods of Bernafay and Trones are 1-2km to the east of Montauban.

4 Oxford Copse and Cambridge Copse were the names given to two small clumps of trees approximately 1 mile behind the British front line of 1st July 2016 and used to conceal artillery positions.

5 The Battle of Bazentin Ridge was fought between 14–17 July 1916 and resulted in the capture of the villages of Bazentin, Longueval and Delville Wood. The 9th (Scottish) Division suffered 1,159 casualties in their attack.

6 In Roman mythology, Saturn was said to have reigned over the world in the Golden Age, when humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labour in a state of innocence.

7 The Colchian Dragon was a giant serpent which guarded the Golden Fleece in the sacred grove of Ares in Kolkhis (Colchis). When Jason and the Argonauts came to fetch the fleece, the beast was slain by the hero or put to sleep by the witch Medea. The monster’s teeth were harvested by King Aeetes for their magical properties. He commanded Jason sow them in a sacred field of Ares with a plough drawn by fire-breathing bulls. When they were seeded a tribe of warlike men (Spartoi) sprang up full-grown from the earth.

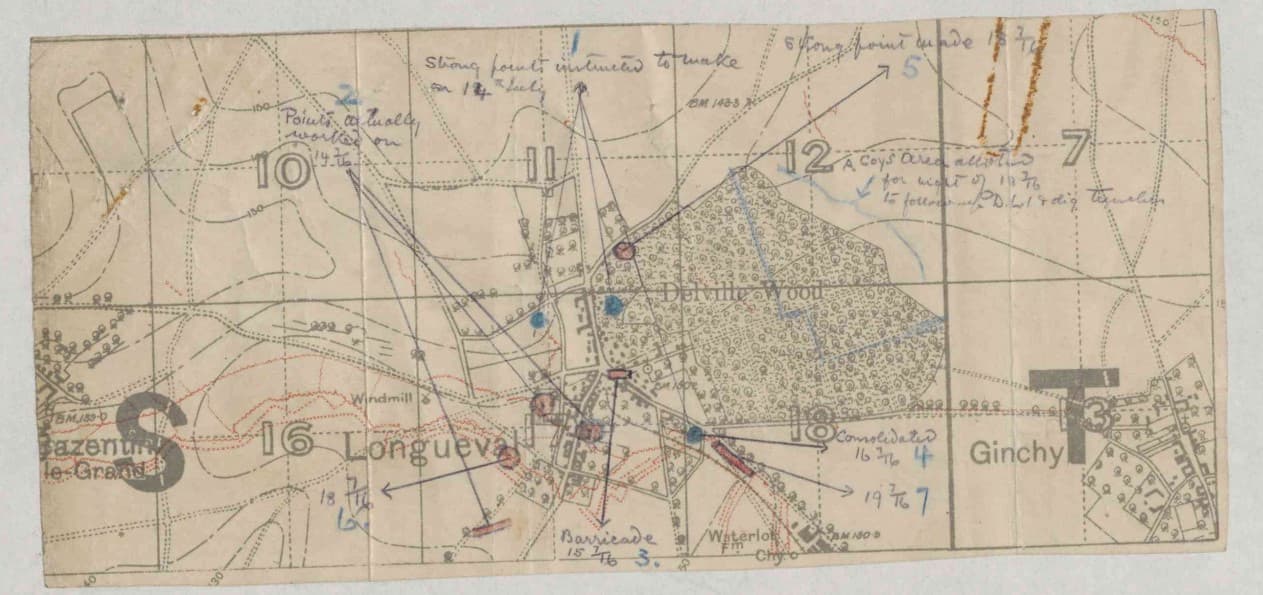

For the first two weeks of July the 9th Seaforths consolidated the capture of the Division’s first day objectives: the village of Montauban. A Company laid a light railway track from Carnoy to supply Montauban, B Company repaired the Maricourt to Montauban road, whilst C Company dug communication trenches to and laid barbed wire entanglements around Bernafay Wood, just to the east of Montauban. This relatively light work all changed on 14th July, when XV and XIII Corps were ordered to spearhead the next phase of the offensive – the capture of the German second line of defence along the ridge stretching from the village of Bazentin, around Longueval and on to Delville Wood. The 9th Division were placed on the right flank of XIII Corps, 26th and 27th brigades targeting Longueval itself with the South Africans attacking Delville Wood.

At 3:25 am, after just a 5 minute opening artillery barrage, the leading Battalions moved forwards. The Germans were surprised by the brevity of the bombardment and the rapid onset of the British troops behind a creeping barrage of high-explosive shells. They made a determined defence but by 10:00 a.m. the 9th Scottish had taken Longueval, except the north end and a strong point in the south-east of the village, which resisted until attacked by the 7th Seaforth and the 5th Cameron Highlanders. It proved impossible to capture Waterlot Farm at the south-east of Longueval and so Delville Wood became a small salient surrounded by the enemy on three sides and bitterly contested over the coming months. Over the next few days the 9th Seaforths constructed strongpoints around Longueval and communication trenches to Montauban. Captain Stuart Forbes Sharp, commanding A Company and writing in the battalion war diary gives a flavour of the work:

“15th July 5am: No. 1 and 2 Platoon left for Longueval. No.2 (Lt Griffith) working on Centre Keep, connecting cellar with dug outs & consolidating. No.1 (Lt Druitt) proceeded to S.18.C.1.9 but were driven off by MG (machine gun) fire at close range – reported to Col. Gordon and platoon was sent back. At 2 pm I took up Lt Walker and No. 3 & 4 platoons to Longueval & reported to Col. Gordon, and as the proposed sites for strong points were still held by the enemy we built a strong barricade at cross road S.17b.5.4.”

On 20th July, after five weeks in the field and much of that under enemy fire, the battalion was withdrawn to Boie-de-la Haie for a much needed rest and refit. An indication of just how tough the pioneer work on the Somme had been is evidenced by the 19 pages of the Battalion war diary covering July 1916. Most months averaged only 4 pages.

Today the area around Bazentin and Longueval has returned to rolling fields of farmland dotted with small rural hamlets. The trenches and shell craters of 1916 have long since filled in and the devasted villages completely rebuilt. But reminders of the war are never far away, whether these be the Commonwealth War Grave Commission’s neat little cemeteries or the countless memorials to British, French and Commonwealth dead. One of the more striking is the Piper’s Memorial erected at the crossroads in Longueval, close to the site of the barricade constructed by A Company on 15th July 1916. Erected in 2020, this ghostly white statue of a highland piper emerging from the trenches stares out towards Waterlot Farm.

Zem Zem’s Lines to the River Somme were written in October 1916 when the battalion were resting at Villers-au-Bois, well back from the Somme front. It is a reflective piece, and like many of his poems contrasts the inherent beauty of the natural world with the horrors inflicted upon it by the war. His description of a dead German soldier is one of the most graphic verses in all of his poetry. Like many of his generation, he ends the poem on a philosophical note, pondering whether the enormous sacrifice will lead to a better Europe – a reflection on the perceived view that this was the War to end all Wars. At around the same time he wrote a more desolate piece entitled The Somme Revisited. It’s not clear whether this was referring to the first poem, or if he did indeed return to the Somme battlefield when he left the 9th Seaforths at the end of October. But perhaps on this occasion the last word should go to that other, more famous Seaforth poet, Lieutenant E.A.MacKintosh, MC. Inscribed on the base of the Pipers Memorial are the lines from his poem Cha Till MacCruimein (Farewell MacCrimmon):

The pipes in the street were playing bravely,

The marching lads went by

With merry hearts and voices singing

My friends marched out to die;

But I was hearing a lonely pibroch

Out of an older war,

“Farewell, farewell, farewell, MacCrimmon,

MacCrimmon comes no more.

By Craig Durham, Volunteer at The Highlanders’ Museum (Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection)